002 EPIGRAPH

“Tocqueville ... envisaged his recollections ... as a sort of ‘mirror’ ... not as a tableau ...” (Traverso, E., “Singular Pasts, the ‘I’ in Historiography”, Columbia University Press, p. 15; 2022)

“... mirrors can never be trusted. The mirage which they produce warrants a critical eye, as they shift left for right and history shows how common and dangerous such shifts are. We need Ferrarotti’s strength to “prefer not to understand, rather than to colour and imprison the object of analysis with conceptions that are, in the final analysis, preconceptions”. (Radović, D., Subjectivities in Investigations of the Urban: the Scream, the Mirror, the Shadow, Tokyo: flick Studio, p. 22; 2014)

(Alas, at present, Substack has no ways other than bold and capital letters to highlight the words! That is why parts of the texts that follow, unwantingly, SHOUT!)

002 i ON ALL OF THIS – setting the scene

How to begin this Work without imposing any a priori logic, as its own logic should emerge through the very processes of thinking and making? That is an URBANISTIC question par excellence, and appropriately so. In the broadest sense, here we deal with the question of cities. We will problematise urban phenomena by asking what cities are, what towns are (what cities want to be-come, what towns want to be-come) and, ultimately, what makes cities – cities, what is that defining quality which other settlements lack, which I shall name URBANITY.

urbophilia@Substack is imagined as an expanding compilation of the variously (un)formatted, (un)finished essays, stories, my stories (thus, to you - his stories), posted with an aim to provoke and to stay open to in(ter)vention. (The stories about) cities are always like that. In any storytelling LANGUAGE and TRANSLATION are of paramount importance. In a way not dissimilar to languages, cities are among the most complex and truly global expressions of the humankind. In order to surrender in front of their complexity, I often reach back to the Felix Guattari’s remark how, “when we think about cities, we are always thinking about something else.”

urbophilia@Substack is written in English language. In which language are my texts thought ... I cannot know. From the very first sentence here it must have been obvious that I was not born into this language. Long ago, without much thinking, I chose to learn English only to, much later, find myself talking, thinking, living that language, thrown into it (in a quite Heideggerian way).

My cultural experiences arguably are quite unique. That came about neither only from my interests nor by choice, but also from diverse (un)intentional immersions, accrued lived experiences from places the founding cultures of which were radically different between each other – and from that of my own (say Global South-Easts, to which we may return later). Background(s) and realities of life can never guarantee the depth of insights; to reach there, one must work hard. But challenging conditions do generate some good questions. Here I want to explore critical questions related to dialectics between cultural belonging and foreignness (including the belonging and foreignness of my own), even the complete alienness, brutal thrownness (into the world). For my research importantly, albeit at personal level sadly, that (as rough as “Geworfenheit” sounds) also applies to the culture I have originated from.

Arundhati Roy formulates nicely how English language “allows other ‘music’”. Such quality I seek here. A counterpoint – as in Latin contrapunctum, as in Huxley’s “Point Counter Point” (which I have first read as “Kontrapunkt”), as in music – counterpunctual interplay of thought and communication. Even if I could depart from my broken accent, my oft alien syntax, a palpable inability to get my articles right, I would (arrogantly, perhaps) keep those imperfections. While this language in which I for decades live is not mine (none of the languages which I use truly is), the ideas which it helps me express are my ideas. In those imperfections my language(s) coexist. I promise, I will not use ChatGPT and other inhuman artificial subtleties, to spare you from my crude formulations.

The most interesting of questions that frame human nomadic existence is the syntax of thought. In which language do I think – I do not, I cannot know.

Here I will briefly digress, only to point at the importance of not understanding. I lived in Japan long enough to comprehend, and to accept, that I am the odd one out (there), the radical Other. Roland Barthes masterfully captures the importance of full immersion into “the murmuring mass of an unknown language (which) constitutes a delicious protection, envelops the foreigner [...] The unknown language, of which I nonetheless grasp the respiration, the emotive aeration, in a word the pure significance, forms around me, as I move, a faint vertigo, sweeping me into its artificial emptiness, which us consummated only for me [...].” We will be returning to Barthes.

While languages structure our perceptions of reality, they themselves get constructed by broader realities of life. Akin to Lefebvre’s understanding of cities as projections of society on the ground, languages eloquently express the ways in which we see and experience the world around us. These essays, written and read in English, will be complemented by some visual, non-verbal essays and fragments in other languages in which we (can) equally feel, listen, observe, and communicate. I tend to proceed with an acute awareness of difficulties, even an outright impossibility of translation – especially when it comes to the most profound, subtlest nuances in communication. More about that is to follow. At this moment I only point at sensibility with which urbophilia@Substack is to be built.

002 ii ON SENSIBILITY – a prologue

The SENSIBILITY of urbophilia defines a particular, action-orientated way of thinking, in search of the ways beyond established routines, a true methodos (μέθά + οδος). That search does not begin here. The key framing concepts of my work in that field are: (a) urbophilia, (b) the right to the city, (c) eco-urbanity and radical realism, and (d) contextualisations. With several brief stories and longish extracts from my relevant books and papers, along with one inspirational classic, I will provide what is needed to begin.

(a) URBOPHILIA

As stated in my invitation to urbophilia@Substack, the sensibility and the theme that inform the Work, are encapsulated in that single word – urbophilia. This coinage of Latin “urbs” and Greek “φιλία” engages both the complexity of the phenomenon named, and proactive attitude, an unconcealed praise of the condition of urbanity.

That term made its way into my work in the early 1990s, as a defensive move in response to urbophobia, the fear and hatred of cities which shook my world. Those frightening times were marked by an resurgence of destructive, atavistic forces of ancient, even mythical origin which descended upon the culture(s) in which I was born, formed, and which I loved. While investigating the reasons why in certain historic periods and regions cities become feared, hated, attacked, and destroyed, I realised how precisely an understanding of dialectics between the hatred and its diametrical opposite, love, could lead to better understanding not only of what the cities are, but also of what the cities could and, most importantly, what they should be(come). At that time, in an essay written at the University of Melbourne, drenched in flood of conflicting reports from thousands of kilometres away, with still strong bodily memories from the student street protests – I could understand and summarise how “the cities were attacked and destroyed because they were cities, because they embodied the pluralist, cosmopolitan, inclusive culture that ridiculed the narrow particularism and xenophobia of nationalistic exclusiveness. [...] The internal, anti-urban forces denied the citizens [...] their right to the city, that essential, complex ‘right to freedom, to individualisation in socialisation, to habitat and to inhabit’ [Lefebvre, 1996]. At the same time, [...] external forces denied the people [...] their right to choice. A silence that followed the tragic coincidence allowed those cities to be destroyed.”

As I repeat those words here, in 2024, we witness the history of (in)human hatred of cities tragically repeating itself.

My research into such, unthinkable yet real nadir of human nature has juxtaposed, and it openly celebrates the opposite, the very heights of civilisation, expressions of the innately human abilities to create and – to love. Yes, research must stay objective but, also – yes!! – “impartiality” should never sacrifice the basic civilisational values.

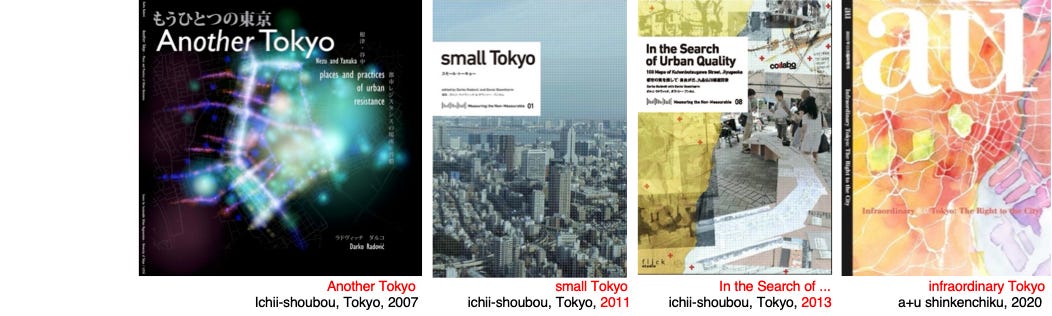

Thus, by bringing two idea(l)s, those of the city and of love (philia) together – “urbophilia” has emerged, soon became a title of the book (University of Belgrade, 2007), then of a newsletter (co+labo.radović, Keio University, 2009-21), still published (co+re. partnership Tokyo.Bangkok.Milano.Ljubljana; since 2021). As my key contribution to an exciting and inspirational Philips Think Tank for Healthy and Livable City (2010-12), I have reframed “urbophilia” into an activist “Lovable City Hypothesis”, which remains at the core of my efforts ever since – and of the Work here.

(b) THE RIGHT TO THE CITY

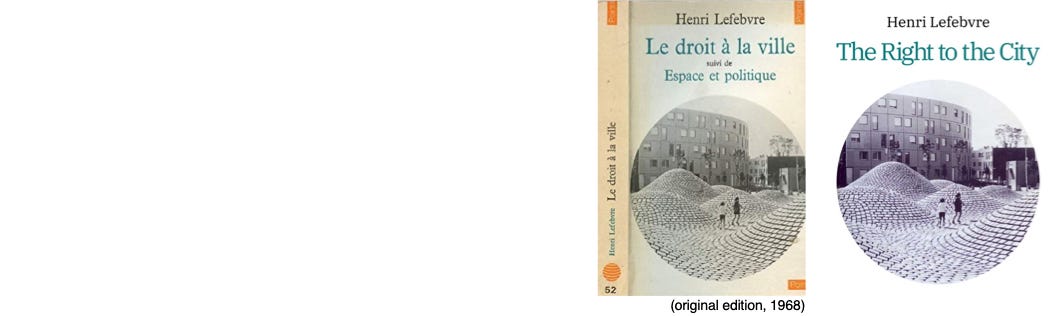

By also bringing two terms – the rights and the city – in a teasingly close, Michelangesque proximity, Henri Lefebvre has captured the political essence of urban condition, his key point that there could be no empowered human existence without urbanity, nor cities without the emancipated citizenry (Le droit à la ville, 1968).

The right to a concrete city is, as quoted above, an essential yet immensely complex “right to freedom, to individualisation in socialisation, to habitat and to inhabit”, the right to formulate and to make choices. Such approach to cities and politics helps us see cities as politics, precisely as the original, ideal (never lived) poleis (πόλεις) wanted themselves to be.

Of course, the Right to the City is best defined by Lefebvre’s own words. But even severely cut (as, alas, in what follows here), his position that “the right to the city is like A CRY and A DEMAND” gives full taste of an imperative – to be(come) urban. He writes how “the right to the city cannot be conceived of as a simple visiting right or as a return to traditional cities. It can only be formulated as a transformed and renewed right to urban life. It does not matter whether the urban fabric encloses the countryside and what survives of peasant life, as long as the 'urban', place of encounter, priority of use value, inscription in space of a time promoted to the rank of A SUPREME RESOURCE among all resources, finds its morphological base and its practico-material realization. Which presumes AN INTEGRATED THEORY of the city and urban society, using the resources of science and art.”

That thought (as action, towards action) complements one of Lefebvre’s famous definitions of cities (characteristically, a triade), in which he proposes [...] a first definition of the city as a projection of society on the ground [...] What is inscribed and projected is not only a far order, a social whole, a mode of production, a general code, it is also time, or rather, times, rhythms.” Then […] “another definition which perhaps does not destroy the first: the city is the ensemble of differences between cities.” […], and still [...] “another definition, of plurality, coexistence and simultaneity in the urban of patterns, ways of living urban life.”

These truncated prompts frame one of the key questions (which I want to open here, and revisit later), the question of the relationship between an IDEAL (as touched upon above) and CONCRETE cities, where vécu, the quality of the actual lives actually lived, becomes dreamily asymptotic towards an exemplary urbanity.

(To those interested in cities I recommend reading Lefebvre’s, richly digressive, engrossing oeuvre without mediators [along with few valid interpretations; recently Schmid, 2023] – to which I love to return, for inspiration.)

(c) ECO-URBANITY and RADICAL REALISM

The concept of eco-urbanity, later coupled with radical realism, was formulated during my professorship at the University of Tokyo (2006-08), when I proposed it as a theme for what was to become a memorable symposium, a gathering of the select group of professionals and academics from all over the world who came to the Centre for Sustainable Urban Regeneration to – think together. The product was a book “eco-urbanity: towards well-mannered built environments” (as in “urbophilia”, all in the lowercase letters).

In the opening “Framework of an Idea”, I highlighted “the urgency of a radical shift towards ecologically responsible urban development, and also put forward a reminder that it is critical to remember the other side of the dialectical couple which constitutes acceptable development – cultural sustainability. [...] Both the ecosphere and the socio-sphere are endangered by the same forces, which are often represented as one of many expressions of globalization.” A detailed introduction elaborated how, “from Harvey’s Lefebvrian tripartite definition of globalization as process, condition and political project emerges an understanding of globalization as the geographical reorganization of capitalism: in other words, the old story, rewritten large, with recognizable patterns of re-energized colonialism and the continuity of established power-structures, and their combined unwillingness and incapacity to change their course.” I felt obliged to stress then, as I have to do again, almost two decades later, how “that picture, combined with the necessity of radical change, does not leave much space for optimism. It seems that the very term globalization has become compromised to the extent that we may need new words and new concepts that are open enough to facilitate the emergence of new agendas. [...]

Focusing on cities, this book deliberately merges ecological/environmental and cultural/urban sustainability, and recognizes their (ideo)logical flow into – eco-urbanity.” That is what I want to bring to urbophilia@Substack.

Precisely like urbophilia before, term eco-urbanity is a coinage. It connotes an imperative, a demand for co-productive dialectisation of two critical phenomena, in search of harmony. The Postscript has summarised how “eco-urbanity never separates the measurable and the non-measurable. It aims to grasp the totality of the urban, the full complexity of the Lefebvrian oeuvre. [...] quantitative and qualitative aspects of spatial quality are densely interwoven, they reinforce or critically question each other. eco-urbanity remains an opera aperta.” [...] “In the world of an increased eco-cultural responsibility, locally responsive environments do not deny the importance of universalizing forces. On the contrary [...] it is exactly by confirming their local identities that cities and architecture reach true global quality. The environmentally and culturally responsive and responsible spaces, buildings and activities that make such cities are spatial expressions of eco-urbanity.”

Sadly, that is where we still are, restricted to muted, increasingly digitalised (sterilised, aestheticized) cry ... but still capable to, and expected to demand!

During my years at Keio University and ever since, I sought ways towards the much-needed radical change. eco-urbanity sets robust theoretical grounds for such endeavour, while radical realism innovates praxis. Thought and action, the relationship between which is never monodirectional, seek ways to test and to enrich each other. RADICAL REALISM IS THE PRAXIS OF ECO-URBANITY. The most recent co+re.partnership project, exhibited in the Pavilion of Monte Negro at La Biennale Architettura in Venice (Boontharm, Radović, in “Mirages”, 2023) under the title “A Positive Arrogance Hypothesis”, included a Radical Realism Manifesto, pointing at some arguably easy, certainly possible and absolutely necessary ways of rethinking territories – under the logical and realistic conditions, which the ruling, simplistic yet immensely powerful political systems declare impossible.

The precondition for change demands a PARADIGM SHIFT in values. I often remind my students to have a look at old photos, and to read the Situationists’ graffiti, to see and to hear the cry of their peers on the walls of Paris in 1968 – Soyez réalistes, demandez l’impossible – be realistic, demand the impossible (to which we will be returning later). At this moment it is important to bear in mind, as summarised in another, older essay, that only “the quality and character of everyday life, together with spatial expressions of ordinary activities are going to be the measure of success or failure on the road towards sustainable development” (Radović, 200?).

(d) CONTEXTUALISATION(s)

Cities are CONCRETE REALITIES. The above discussed select principles of dealing with the urban – urbophilia, the right to the city, eco-urbanity and radical realism need to be SITUATED, critically attuned to particular spatial and temporal conditions, to places and practices lived. Thus, the fourth principle, contextualisations(s), is about ways in which these values and concepts get projected onto actual physical and metaphysical grounds, which we inhabit and in which we all end. For that, strong planning practices (critically founded upon the values of ecological and cultural sustainability) are needed, at coordinated strategic + tactical + territorial + rural + urbanistic + architectural + other design levels and scales.

By definition, contextualisations are particular. They deal with concrete, tangible places, and with the fluidity of real lives lived. My briefly mentioned background and my (life as) journeys were the schools of an immense complexity that surrounds us. That helped me discover the passion (if not always a pleasure) in dealing with contexts – both in professional and academic work, and in life. Various versions of my favourite, nomadic architecture/urban design course “Theory and Practice of Urbanity - TPU” followed me to, and were crafted by and for the lecture theatres and design studios across three continents, and some islands. A critical difference between the visits (regardless how well informed one might be) and lived experiences (related to the combined length and depth of stay) remain my obsession. How many times have I repeated, to myself as well and to others, Franco Ferrarotti’s credo, that after all those immersions and expulsions I also “prefer not to understand, rather than to colour and imprison the object of analysis with conceptions that are, in the final analysis, preconceptions”! With such attitude, because of diversity of the Substack readers, I chose to present here several fragments from my work in/on places of radical (cultural) difference in which I used to work and where I lived long enough to not only know, but to love and to be loved. To set the scene for that, I will focus on Tokyo and, using extracts from my “infraordinary Tokyo, the Right to the City” (2020), introduce the flows of thinking-making-living which are central to the disciplines involved in production of space.

To “infraordinary Tokyo” I have invited a group of Japanese and foreigners, colleagues, intellectuals, academics and practitioners, who live in and explore Tokyo, to contribute their latest insights. My own text was conceptualised as an essay consisting of seven essays, a narrative backbone which introduces, leads through, and closes clusters of themes. Our overall aim was to point at and to capture “the essence” of Tokyo, its spaces as lived.

But first – to be invited to edit an issue of the reputable a+u was a great honour, most of all because up to that moment the foreigners were editing issues on foreign architecture and urbanism, while the Japanese dealt with Japanese themes. “I was invited to focus at Tokyo. That recognition of my ways in dealing with this amazing city felt precious. Over the years of living and working in Japan I have learned to treasure cultural difference, the very quality which inspired my move to this country. Both my everyday life and my research are interaction and dialogue-based, aiming to open up, rather than tame down cultural distance. I enjoy radical otherness, as encapsulated in the name of my research laboratory at Keio University - co+labo (since 2009). Our ethos and praxis cherish ‘the dignity of bearing the + sign, that of joy, happiness, enjoyment, of sensuality - the sign of life’ (Lefebvre, 2017)” [...].

My life and work in Tokyo (2006-07, and 2009-21) forcefully confirmed François Jullien’s position that “in contacts with the Other ‘only crossing thresholds and entering might be possible’ (2015). Whenever entering Tokyo, I feel that I am arriving to one of ‘my’ cities. That transforms the limitation identified by Jullien, remaking my physical and intellectual arrivals into a cumulative sequence of re-enterings. True residing here made me involved, possessed not only by desire to learn and know but, preposterously, to also help Tokyo become a better place. [...] That (strange, I readily admit) sense of entitlement, perpetually encouraged by my generous collocutors, points at an emotional engagement with Tokyo which could, perhaps, help comprehend what makes me stay here.”

Under the title “Urbanistic sensibility in thinking and making this magazine” I introduced my own theoretical position (as above, while explaining what contextualised urbophilia, the right to the city, eco-urbanity and radical realism are). I had to stress how “good cities are not made by architects, urbanists, other experts and technocrats, but by their citizens. The complexity of urban phenomena demands active citizenry, variously supported and guided by responsible strategic planning, competent design and management across scales. It is correct that ‘the history of urban design (theory) is that of a continual search for the most harmonious balance between control and freedom, a search for the order which liberates rather than oppresses’ (Ellin, 1996). Socially responsible and responsive order is, in itself, an important urban condition, precisely encapsulated in Jean-Luc Nancy’s, Heideggerian claim that the defining dimension of being human is – being-with (Nancy, 2000). Citizens have both the right and responsibility to shape social, aesthetic, environmental and political realities of their towns, from which an identity, the singularity of their city emerges. That is urban character, a set of fundamental and distinctive, (r)evolutionary changeable characteristics – metaphorically akin to DNA. The right to the city – which subtitles this issue of a+u – is always the right to a concrete city.”

Reaching back to my first efforts to think urbanity of Japan, and ever since “I have consulted the wisdom of Roland Barthes, who also sought to suspend ‘the need to locate Japan in opposition to Western culture’ (Barthes, 1982) while, inevitably, constructing ‘a system which I shall call: Japan’, a system that enables ‘flashes of insight into the complexity of representing the expereince of reality, the reality of experience. Nothing more, nothing less’ (Trifonas, 2001). Such flashes of insight inform and provoke visual and textual essays which constitute this volume. [...] For Barthes the linguist, ‘language will always mediate understanding’ (ibid.). On the other hand, as an architect and urbanist, in order to find, live and (re)search my own Japan, I strive not to reduce experiences to any of their many expressions, seeking an elusive synthesis, the very totality of the urban. I am interested in coexistence of the seemingly opposed realities of the urban – both its totality, Lefebvrian oeuvre, and its particularities which contain the irreducible essence, that (undefinable but sensible) ‘something’ which makes every city particular.“

Towards the end, my chapter “Tokyo Lived: Global Futures” pointed out how “the importance of cultural specificity can not be overemphasised here. Globalisation as an enveloping condition makes everything referential, as never before. In his efforts to philosophise the gap between Asian (Chinese) and European cultures François Jullien suggest écart. Rejecting usual comparisons, he sets ‘cultures side by side [... he] places them on either side of an exploratory divide’ (Jullien, 2018). That offers a way to reposition our thinking about the complexity and simultaneity of urban development. We can conceptualise (re)definition of cultures in the context of an acute awareness of each other – but, without an imperative to establish, follow and copy the models. In his most recent book, De l’Être au Vivre (2020), Jullien places twenty key points of Asian (Chinese) and European cultures along an exploratory divide, many of which are of relevance for our discussion about Tokyo. [...] I believe that this method translates well into thinking about cities and theorising the grounded world class. At a minimum, it helps generate new questions.”

These questions help me enter (and, when spewn out, re-enter), keep on observing and questioning cities, and myself in those cities in, and between which I had opportunities to live.

+ + +

As you probably noticed, the titles of my books listed above – “urbophilia”, “eco-urbanity, “infraordinary Tokyo” – were all, over the years, written in lower-case letters. But then, Radical realism and Positive Arrogance were capitalised. That is my (perhaps somewhat banal, yet important) non-verbal message, an effort to express the humility of thought and toughness of action, facing the urban. Sometimes, the medium indeed is the message.

But, alas, at Substack the only way to highlight the role of lower-case in my work is – to use CAPITAL LETTERS!

CUT!

This essay will be followed by the next ON the Work instalment

003 ON the first person singular – more than a language