_ _ _ this dérive into Midorigaoka (+ Jiyugaoka) starts with a part of my essay from infraordinary Tokyo, the Right to the City (pp. 92-97) . . . here I only highlight and add some images that should help urbophilia readers to better visualise this story; that will be followed by brief discussion and unstructured drifts and dives conducted there over the last several days

TOKYO LIVED: Jiyugaoka/Midorigaoka

“It took me three re-enterings and a combined dozen of years of lived experience to begin consolidating my Tokyo. In Jiyugaoka/ Midorigaoka, the third locus of my long-term residence in Tokyo, now I live the sixth year. Various investigations of this precinct, conducted in and around co+labo radović, within our strategic research project Measuring the non-Measurable, Mn’M (Keio, 2011-14) and its many follow-ups, have pointed at the importance of cultural appropriation the ideal of the public and, consequently, the place of the right to the city in Japanese society (Radović, 2020).

In Jiyugaoka an improbable and (yes, I know – impossible, but heart-warming) sense of home started to emerge. I became aware of that when local politics started to annoy me.

In a quiet, residential Midorigaoka, one of residential extensions of Jiyugaoka, our apartment faces a secondary street. We are, again, only few minutes away from the railway station and all that one needs is within easy, pedestrian or mamachari, cycling reach. The area is as peaceful as Nezu and Ōkurayama were, safe and well maintained, enjoyable to live in but, as one would by now expect, in yet another way. Although central, as the peripheral Ōkurayama this precinct was rural until the late 1920s. Just as over there, only few years after the Great Kanto Earthquake the settlement started to emerge in the rice fields. As elsewhere in Tokyo, a true urbogenetic sparkle came with railway, here supported by the newly established Liberal Hill School. The name Liberal, or Freedom Hill was referring to the spirit of the short-lived Taishō democracy (1912-26). The station opened on my birthday (albeit several decades too early), on 28 August 1927, triggering a predictable pattern of growth, further enhanced when Tokyu-Toyoko and Ōimachi Lines established an interchange there. Central Jiyūgaoka took its present form around the 1970. For a non-Japanese researcher fascinated by language it was interesting to find that the newly acquired status was confirmed by inauguration of the official spelling of its name, as 自由が丘, in 1966.

Jiyūgaoka now ranks among the top residential precincts of Tokyo and boasts a highly recognizable shopping precinct. Fine residential areas are within walking distance from the Station and an extremely commercialised centre. Although popular, central Jiyugaoka keeps its fine urban grain and resists the onslaught of bigness, the destiny of all important railway hubs in Tokyo. A distinct Jiyugaoka charm reaches beyond comfortable lifestyle and fashionable shops. Its qualities include an obvious attractiveness for young women, couples with small children, presence of subtle (and increasingly not so subtle) tourist spots, an evident passion for groomed dogs, booming café culture, carefully organised and managed open-space programmes, pedestrian-friendly weekends, regular local festivals, several places of distinct environmental quality and one which combines the whole lot – Kuhonbutsugawa Ryokudô (Radović, Boontharm, 2014) [...].

The sinuous, 2.2 kilometres long leafy promenade connects three railways stations. Central segment of this spine is shopping area, while the rest remains predominantly or exclusively residential. The street was built on the top of Kuhonbutsu River and, very much due to that move (and [...] skillful navigation through gray areas of Japanese planning and legal systems), today that is one of the most pedestrian-friendly spaces in Tokyo, the backbone of an interesting local lifestyle. The life in and around Jiyugaoka provided me with valuable lessons about Japanese culture and urbanity of Tokyo, and posed an even bigger number of questions. The steepest learning curve came from our involvement with local community, through installations of co+labo Mn’M urban research pavilions in Ryokudō, and various interactions with their influential and capable machi zukkuri organisation.

That place remains in focus of co+labo investigations, including complex spatial thresholds, the passages from exclusively residential, Nezu-like quietness, via variously nuanced mixed-use segments, to one of the most popular consumption hubs of contemporary Tokyo. It is equally interesting for research of Japanese proverbial cultural importation and translation impulses (Tatsumi, 2006). For instance, in Jiyugaoka everything has to be ‘French’. There is even a Marie Claire Street next to the Station! But, to me the most interesting was the most improbable of imports, that sense of proto-public quality which started to permeate the air of Ryokudô (Radović, 2014), along the other side of the coin – ubiquitous, deliberate signs of control and prohibitions, unnecessary restrictions to any kind of spontaneous behaviour.

One of my ‘Obs. J.” notes (which, depending on mood, I interpret as Observing Japan or as Obsession Japan), quotes an advice by George Perec: ‘Try to observe the street, from time to time, perhaps in a slightly systematic fashion. Apply yourself. Take your time. Note down what you see. The noteworthy things going on’, advices (Bellos, 1993) and elaborates now: ‘drinking my double espresso in front of La Manda café (where the idea of Mn’M Jiyugaoka project first emerged; first photos, strip above) and observing Kuhonbutsugawa Street, I notice teenagers who, sitting on the benches, in the heat of discussion, take their shoes of and fold their legs – feeling at home; I see an elderly gentleman who, in discussion with his neighbour, takes full bench to lie down and stretch his back; there are people reading (more often a book, than a mobile phone the most common ’reading’ material in Tokyo these days); mothers hugging, some feeding their sleepy babies; children playing; there are pigeons, as opposed to, elsewhere in Tokyo, ubiquitous crows. Spaces are starting to be used creatively, in unplanned ways; several vans serve coffee, crêpes, and stimulate senses other than sight. More and more restaurants offer alfresco service, which would, only a couple of years ago, be labeled as ‘non-Japanese’.

[…] Those anecdotes add up to illustrate one of the most interesting processes which seems to be spinning up the cycle of causation in Kuhonbutsugawa Street and showing how those spaces might, indeed, possess critical transformative capacity. An embedded potential and, importantly, evident care for those urban environments stimulate desire for creative and free expression. That desire might, indeed, be exactly - a desire for urbanity. In that case, the quality which seems to be emerging in this Promenade would be reaching towards practices of appropriation of urban space which, as in Lefebvre’s powerful definition of the right to the city, are “the right to the oeuvre (participation) and appropriation (not to be confused with property but use value) …” (ibid.). Appreciation of urban conviviality, of the Nancean being-with (Nancy, 2000), which is the main constituent of urbanity, might be emerging in Kuhonbutsugawa Street. That culture bubbles amidst the mono-culture of an extreme consumerism, surrounded by the confronting superficiality and seemingly insatiable appetite for fakeness (it should suffice to say that in Jiyūgaoka there is also a fake gondola, in an appropriately fake canal, next to the fake piazza, in a scaled-down, fake ‘Venice’) (Radović, 2014).

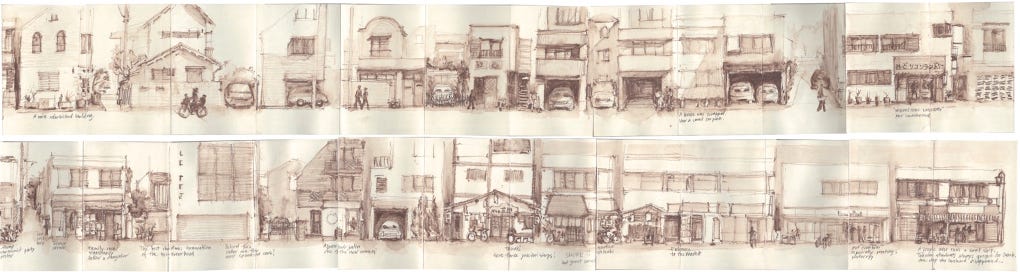

_ _ _ Davisi Boontharm’s orihon “street with no name” (below) captures that unforgettable, low-key, everydayness of our street in Midorigaoka (first published in co+labo urbophilia, 2019), our Japanese città slow

_ _ _ from journeys and from home, shinkenchiku-ka Gallery (Tokyo, 2.2025)

Although that a+u essay focused at Jiyugaoka and Midorigaoka, Jiyugaoka dominates. Midorigaoka gets a few words there, and precisely that is IT! That “lack” points at critical qualities of our modest, residential Midorigaoka, of a slow, deep life there. The character of that precinct gets defined not only by what it has, but by proximities, by being situated not far from the commercial area, not far from the railways station, not far from a variety of attractions and activities – yet simultaneously far enough from them all, enough not to be affected by unwanted rush, noise, at distance which allows interaction by choice, not as an imperative (that quality, the human scale, reminds me of urbanity I was born into; Google tells me that it is 9,466 kilometres in a straight line far from Tokyo and yet – so palpably “same”, human[e]). The quality of a predominantly (not exclusively!) residential Midorigaoka is in complexity of its integration, in polyfunctionality of its broader urban fabric, in that archipelago of urbanities (felt in my first encounters with Tokyo, mentioned in dérive II) to which it belongs, and which belong to it . . . what Jiyugaoka has, Midorigaoka can chose to have – or to decline; that very choice constitutes a key difference, its exclusive (and excluding) qualities

_ _ _ to me, to us, Midorigaoka (+ Jiyugaoka) was (were) about living . . . loving . . . fully, about the definable and undefinable realms of life combined, about coexisting measurable and non-measurable qualities of the urban

_ _ _ I knew that, attractive Jiyugaoka from my early encounters with Tokyo; Ōkurayama waited to be discovered; (and discovered it was, by chance, during one of my Measuring the non-Measurable drifts when, while exploring and getting lost in an ordinary street with no name, I came by a house painted white, and “Apartment for rent” sign)

(above is the record of that Mn’M dérive, when I stumbled upon the Lighthouse which became our base for the years to come)

NOW . . .

_ _ _ IF Nezu indeed was about falling in love (with one, to me exotic urbanity, a town lived),

_ _ _ IF Ōkurayama was my surrender to a particular beauty (of one singular building, of architecture lived),

_ _ _ THEN Midorigaoka was all about totality (the wholeness of being with, of living in, of a life lived).

OR

_ _ _ IF Nezu and Ōkurayama have provided for my full immersion into an urban culture (the complexity of) which was unknown, alien, fascinatingly different, yet somehow permissive and open to me (with all of my weaknesses, as a total stranger – there), as two truly extraordinary places

_ _ _ THEN Midorigaoka (in organic continuity with Jiyugaoka) has opened (itself) to me (as) an ordinary Tokyo

_ _ _ snapshots from the other day ago, back there, in Kuhonbutsugawa Ryokudô . . . a rainy evening . . . deserted benches . . . La Manda Café used to be somewhere in the middle of that white fence, top-right below . . . still a construction site ?! some local, machi zukkuri conundrum must be slowing it down

_ _ _ our kaiten sushi restaurant . . . again, an “ah, you are back” knowing smile, it does feel nice to be recognised

_ _ _ and back again, on a fine day . . . it’s a working day, no one is out . . .

_ _ _ a winding Ryokudô rewinds memories . . . walking from central Jiyugaoka to our slow Midorigaoka . . .

_ _ _ continuities, nothing has changed, grain, volumes, rhythm . . . (yet. . .)

_ _ _ a sideway (image 3 above), voilaI ! an opening to our – Lighthouse . . . (image 4)

_ _ _ our Lighthouse proudly stands out . . . (my mamachari and V.’s bike are probably still inside, unwanted, unclaimed, rusting) . . . our street . . . a lot has changed, a lot is in the process of change; it seems that the prefab, off the shelf “architecture” takes over; next time we might see the printed ones, too . . . prefabricated “plastic’ ones do not age, they can not remember, never acquiring a sense of age . . . they remain ageless, characterless products always, until new regulations declare them old, have them replaced in the same way in which new mobile phone replaces the old one . . . products, rather than homes, entities rather than identities . . .

_ _ _ “oh-my-god”, yet another house which we knew was knocked down . . . “you also can’t remember it?” . . . “check Google Earth, they might have not updated the street-view yet “ . . . but, alas, soon they will . . . the “brain” of the tech is always in the now, it erases the past, the past of which the very fabric of our consciousness, values, identities are made, the very fabric that we are

_ _ _ ordinary, infraordinary qualities are not obvious at the first glance; they grow on you as time passes by . . . a knowing glance of a neighbour with whom we never spoke, who has never spoken to us, but whose very presence used to make us feel safer, at home . . . and her smile the other day when, after a long time, our eyes met as they used to meet before, in front of her house (one of those ordinary houses which on their own do not signify much, but contribute to an atmosphere, to a whole street, the block, to a certain sense of co-belonging there, in us

_ _ _ and off I go, back in Kuhonbutsugawa Ryokudō . . . re-constituting, re-living my Obs.J (Observing / Obsession Japan) moments . . . a logical question arises: why am I doing this? . . . a too logical question . . . I have just set on one of the benches, taking photos, failing to sketch, trying to catch (up with) the rhythm of that street, to identify the noteworthy, taking notes with no purpose other than to be there and (in a way) to be back then; slowing down . . .

_ _ _ for the end . . . a glance into wider neighbourhood . . . as often, as in Nezu the other day, as before, we escaped to a quiet Jiyugaoka Jinja compound . . . to buy omamori . . . that reminded of co+labo collaboration with local machi zukkuri association . . . their storage, from which we borrowed some of the equipment for our research pavilion is still there (top row below, left). . . remembering my intensive learning, without/ beyond language, about Japanese urbanism, about micro-politics of space . . . moments of consensus and, sometimes, silent/ silenced dissensus . . . . their generosity, along with a simultaneous, deep self-interest . . . retreating to a “pub”, making me drink whiskey (although I would prefer any other drink, but – it seems that, a gaijin had to play a role of shy whiskey – drinker) . . .

_ _ _ sounds of shishi odoshi . . . purifying water (reminds me of Kanazawa, triggering memories)

THUS . . .

IF YaNeSen was a sensibility, a certain nostalgia which I like – I still feel it there

IF Ōkurayama was a aesthetic envelope, a singular touch when it really mattered – that feeling is no more

IF Midorigaoka was about quality of immersion, of being there – that moment is gone

. . . who am I to judge ?! . . . another accidental passer-by must have already stumbled upon it, decided to give it a go, now enjoying pleasures of good orientation, of low winter light penetrating the room . . . or, a sararimen having no time for that

. . . while living there, I was the judge . . . the key is in living; full living is – living with, an inspirational, life-giving partnership . . . that quality judges

. . .urbophilia dérives IV, VI and VII reflect upon three urbanities in which we lived our homes . . . that creates a place; external circumstances may add quality, new opportunities for the depths and heights of what the socius is

CUT!

THUS . . .

. . . learning from the experiences touched upon above: rush as little as possible . . . or, don’t rush ! . . . slow down, take it in . . . BE ! . . . BE there . . . remember Perec ! . . . one can not see IT, experience IT all, one can not feel IT all anyway . . . see(k) the noteworthy . . . come again . . . what is noteworthy? . . . what the noteworthiness is? . . . when . . . where . . . for/with whom . . . why? . . . add to Perec, by observing yourself, there, by contemplating your foci, by framing your own (un)intended . . . ask (why, when, where ... who, who are they, who am I [t]here) . . . the questions arise, broader questions, questions other that those framed by the project at hand (the project which might be the life itself)

. . . does search for meaning destroy simple pleasures of being there?

. . . does search for meaning destroy the pleasures of simply being there?

. . . a Delphi dictum: γνῶθι σεαυτόν . . . know yourself, remains

and . . . off I go, another flight . ..