__ __ __ __ in memoriam, Vladimir Jorga, a friend and 空手家

with this post, we are starting a climb up, (to me) a special segment of our urbophilia journey; regardless how much I wanted to communicate these ideas unedited, alla prima, parts of what is to follow had to be laboured; parts do stay heavier than desired, you are going to feel that; this post has to deliver a rounded story, yet end – unfinished; that is deliberate; not finishing (it) was a point

_ _ _ in general terms, we will continue along the two lines of thought – exploring (i) the ways and formatting of reading, writing (urban) complexities (as in orihon, palimpsest, as in playing with inserts, cut-outs) . . . and (ii) the conundrum of simultaneous subjectivity and (im)possibility, (un)avoidability of the personal; the focus stays on the roles which “I”, that inevitable “me”, plays in our every thought and act

. . . therefore, we proceed with (in)betweenness, multiplicities, compliances, complicities . . . in relation to (in)sensibilities of impression/expression . . . we depart towards the question of potentialities, the depths that such discussions can take us in, the heights to which they might elevate us – always returning to the theme of urbanity, but with (re)fresh(ed) eyes and minds; in order to eventually return, we need to depart from cities

. . . the story of non-finito is such departure, an entry into my way of thinking, making, living the urban – in both practice and academia; it builds upon learnings from my lifelong fascination with one person, an artist, architect, a phenomenon, a field of energy that is – Michelangelo Buonarotti . . . a territory to dérive . . .

. . . so, here begins a story that is impossible to tell (thus, perhaps, in the spirit of non-finito itself), the story of non finito, the very foundation of the enigma Michelangelo or – of the answer Michelangelo

I an enigma

Most of what I know about Michelangelo Buonarroti came from books, from modest and glamorous volumes, visually or only textually rich, from diverse exegeses, lateral reflections, fragments of knowledge found in various texts, heard in lectures, explorations of what intellectuals, poets, specialists and amateurs had to say about, or inspired by Il Divino. The list of sources (which I would love to, but certainly never will compile) would include all relevant books authored in my language, translations to my and to English language, occasional original titles which I used for precious (ad)ventures into his language. That is why, in my late teens or early twenties, I enrolled and enormously enjoyed an Italian language course (at Kolarac). The main purpose was to satisfy a (naïve, unrealistic yet irresistible) desire to get closer to Michelangelo’s unmediated thought. Huh! To access poetry in/of another language?! That was after my first encounter with Michelangelo’s Le Rime, poetry translated to my language, after memorising an unforgettable opening line Pa kaži mi ljubavi. . . (or something like that . . . Dimmi di grazia, amor, se gli occhi i mei . . . (a folded piece of paper with those words may still exist in an old valet, somewhere in my parents’, now empty home).

Then I could only feel that translation was an impossible aim (not knowing how precisely the [im]possibility of translation was to become one of the central themes in my life and academic research). But, even only enjoying different fluidity, melody, the taste of the original verse on my tongue, the Renaissance Italian words and stanzas was fascinatingly sensual experience (the fact that Italian term la stanza stands both for a group of lines within a poem and for a room could, for an architect, be a beautiful opening).

In any case, my passion for exploring Michelangelo’s work continues. Unsystematically I search, and last month I have found an exciting, almost completely visual, photographic volume which deals only with his Pietà sculptures, which I am going share with you shortly, to better explain the key point of this post.

My first encounter with a real-life Michelangelo was in Basilica di San Pietro in Vatican when, with my uncles M. and V., I first visited Italy. I cannot recall when exactly we saw La Pietà, but I vividly remember the feeling, an air surrounding that compression of beauty, and sadness. And a thought that Michelangelo was only twenty-four when he completed this work (which, for many, has completed the Renaissance)! I cannot remember, but I can date that visit with some certainty, as a maniac (whose name should be forgotten) attacked with hammer Michelangelo’s first, and without doubt most beautiful Pietà in May 1972. We were there in summer before that. Alas, so often the ugliest that we, the humans can do preserves memories better that the beauty could.

But, before venturing to that and other Michelangelo’s Pietàs, I need two stories to help me set the scene.

In late 1990’s, more than two decades after my first proper encounter with Michelangelo Buonarotti and his work, I was in Florence, taking part in an interesting conference. But, the streets, Arno and the life of the city were more than interesting. By then knowing Florence quite well, and loving it, I was doing my best to spend as much time as possible out and about, simply feeling good in those spaces with their and, by now, my own memories. At one moment, I entered a shop of an artist, whose beautiful terracotta bianca I knew, where quality resisted the banality of tourist demand (dominated by the “greetings from Florence” kitsch and, at their best, David’s pisselo). I knew that place, but this time it felt special because for the first time I entered the shop with an intention to buy. There was one replica of Michelangelo’s Tondo Pitti, smaller in size, executed not only with precision, but with palpable passion and love, full of something else that has caught not only my eye. A copy – yet a piece of art. As always, in the shop was the owner (I terribly regret forgetting his name; there might still be a bill, somewhere in my faraway, Antipodean place; his negozzio has disappeared long ago).

The conversation, which I have initiated and which the artist accepted with due diligence of a merchant, kindly, vaguely interested in what this, somewhat familiar, potential customer believed to know about Michelangelo and about that particular terracotta. He was responding to my questions, feeding my curiosity, surviving my clumsy ventures into his language until one (precious) moment when he started asking me . . . he was interested in the source of something that I have just said, puzzled by my strange interest in Michelangelo who, he confessed the obvious, was a beacon in his own art, a life-long passion . . . our conversation led to an almost complete neglect of several tourists who wanted to negotiate the price of souvenirs . . . and then, he asked aspetta, aspetta ... he brought me out, locked the shop, and escorted me to his nearby atelier; inside was . . . the real stuff, the results of a lifelong passion, his learnings from Michelangiolo; my host took me by surprise theatrically unveiling an incredible bust of David (. . . so big that his forehead was at the level of my eyes . . .) pointing out how that was an exact, real scale replica and almost screaming: ma, e vouta, e vuota . . . that is an exact replica, but – it is empty! . . .

and . . . that was it

. . . that was IT . . . or, rather, an absence of IT, an absence of that special something which makes art – art, of something that makes a genius – what only a genius can make; the quality that works of other artists may precede, announce, lead towards, gather, learn from and proliferate – as they are the artist almost able, but only almost able – to achieve it themselves . . .

. . . e vouta, e vuota . . . I cannot remember, but I must have fallen silent; I do not remember, but my host must have fallen silent, too

. . . he has just shown to me at what was not there

. . . something that, only hundreds of meters away, radiated from the original Il Gigante . . .

. . . this magnificent replica, its head, neck, sharp eyes and curve of the shoulder (in height almost my size), all that was done in Carrara marble; real, carefully measured proportions were executed in the exactly same, noble stone, as precisely as in the one in Galleria dell Academia (moved there in 1873, from the original position in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, as chosen by Michelangelo himself) was, BUT . . . something . . . something, the spirit of Il Gigante – was not there . . . this bust was empty!

e vouta, e vouta, e vouta, e vouta resonated the atelier, as if that stanza itself suddenly became empty . . . simultaneously a cry of desperation (over own failure) and a breath of fascination (confirming artistic substance which only Michelangelo could communicate to a block of stone, to his pietra)

. . . la copia e essata, ma vuota!

II non-finito openings, not closures

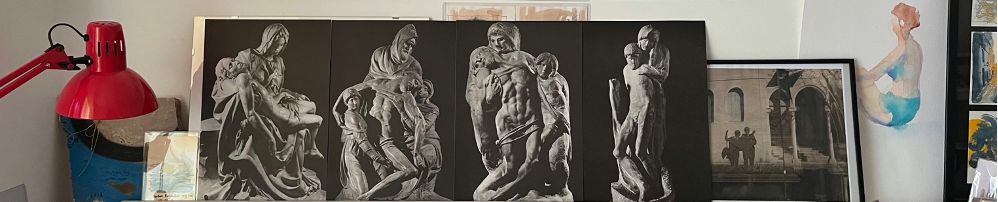

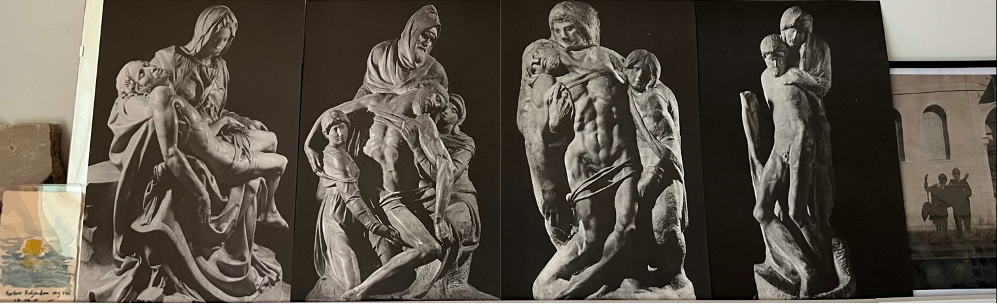

our story can now begin; as stories often do, this one starts from a book, a book mentioned above, Michelangelo e la Pietra: Le Pietà, which I have found recently at an Antique Market in Como; a tastefully crafted, large (27.4x40.3 cm, publ. Ente Fiuggi, 1965) elegant and puzzling volume. A basic description provided by an online retailer suffices here: that is “a large format folder with unbound quinterni (inserts) that deal with Michelangelo's four pietà: Pietà of Palestrina Pietà Rondanini, Pietà of the Cathedral of Florence, Pietà of San Pietro. Each quinterno consists of a front piece with brief introduction with historical notes about the work, and on the inside four large black and white plates relating to the pietà covered in the file. The work is completed by another folder which reproduces 13 facsimile letters written by Michelangelo to his nephew (preserved in the Buonarroti archives and the British Museum), especially concerning his lithiasis and the hydroponic treatment of it; each reproduction shows the transcription in Italian. [...] Author(s) AA.VV. Publisher Fiuggi Publisher Place Frosinone Year 1965 Pages n.n. dimensions 28x40 (cm) Illustrations 16 plates. b/w - 16 b/w plates Binding folder ed. ill. with loose quinterni”

(to discussion of details, including scarce and (seemingly) bizarre ones that accompany the lithiasis segment, we might return later)

the lives of books (and of knowledges)

_ _ _ this book will continue its life (books do have their lives) next to my other Michelangelo volumes, on one of the shelves (alas) scattered over three continents; new contexts, new placings, repositioning related to my work to their current use will make this volume intertwine with other, of variously (un)related contents, with memories which they trigger, their stories and my stories, my fascinations (the reasons of which I address here but will, probably, never understand) . . . as long as there is me; thus, let’s leave my memories for some other occasion

_ _ _ the works presented in Michelangelo e la Pietra are (as in illustration above) (1) Pietà of San Pietro (1498-99, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican), (2) Pietà Bandini (1547-1555, Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence), (3) Palestrina Pietà (cca. 1555; Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence), and (4) Pietà Rondanini (1552-1564/the year of Michelangelo’s death; Castello Sforzesco, Milano); N.B.: hyperlink to Pietà Palestrina is highlighted differently

_ _ _ those pages, scarce in text, strong in austere black-white, dramatically cut photographs by an unnamed author (!?), are fascinating, in themselves a fertile field for stories; in urbophilia, I am interested precisely in such synergies, in overlaps and gaps, in opacities and transparencies (as in orihon, as in palimpsest), even in scars resulting from careful, yet who knows how many times repeated placing of this volume/folder on a street stall in Commo, from my conversation with a bookseller . . . a life of the book; in urbophilia, I am interested in placings that can/might create synergies (in books, as in lives and spaces, in stanze and stanze, in architecture and in cities as in spaces and ideas lived which these books are made to communicate); let’s leave my memories for another time

the lives of books – a digression, on gaps (in/of knowledge)

_ _ _ we rarely have enough space for digressions but, in terms of the history of art, this is a live story; the lives of books can be as interesting as the stories which they communicate are; even books written by authorities in the field remain open; in that sense Michelangelo e la Pietra: Le Pietà has its own, unique story. Only briefly (for additional accuracy of our story) I need to mention how since 1965, when this book was published, the official list of four Pieta’s sculpted by Michelangelo Buonarotti has been reduced to three. Since 1964, attribution of Palestrina Pietà (sculpted cca. 1555; since 1756 described as “a sketch” by Michelangelo) started to be questioned. Alternative attributions have been offered, leading to an official disputation in 1987. The group was and remains exhibited in Galleria del Accademia, but relegated to an “attributed to Michelangelo” status (considered to be the work by Nicola Menghini, or even by Bernini).

_ _ _ this impasse warrants a serious discussion about originality, we have to at least mark the question: what an original is? why an excellent copy – e vouta? (alas, asking that in the times of AI)

_ _ _ but, before we continue . . . let me venture into territories far beyond my expertise and propose a (shaky) hypothesis (only for the sake of thinking as, as we see – not even experts on Michelangelo can judge his work)

the dismissal of the fourth Pietà was based on a belief that Michelangelo Buonarotti, Il divino was able to do nothing less than perfect – while his own dissatisfaction with some of his work is very well documented, even by his contemporaries, immediate witnesses, even aficionados – such as Giorgio Vasari. Famously, Vasari has managed to stop Michelangelo destroying his Pietà Rondanini, unhappy with that way his sculpting was progressing (THAT moment of agony, just before the death of the Master warrants a post on its own . . . I may try). Keen on opinion of generations to come, Michelangelo has famously burned quantities of drawings, leaving only those which he considered worthy of the intended message. He did not need external critics, he was the toughest critic of all. So, Palestrina Pietà might have been one of such works, a sketch which would not survive if he could lay his hands on it . . .

Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps . . . Why? For the sake of thinking . . . Sometimes a premature, or too strong judgments can prevent a good, yet infirm thought to emerge. Or, for the sake of fun; fun can also liberate thought.

Just think of impact that Michelangelo has had on the other greats shaping human civilisation. There is no need to imagine, just read how that man shaped the thought of one of the greatest minds of Modern era - Sigmund Freud (pages 122-150). And . . . Michelangelo has only whispered his vision of Moses in San Pietro in Vincoli his ear in Rome, in Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli). After a brave flight inspired by Michelangelo, the genius of Freud ends . . . with questions: “But what if both of us have strayed on to a wrong path? What if we have taken too serious and profound a view of details which were nothing to the artist, details which he had introduced quite arbitrarily or for some purely formal reasons with no hidden intention behind? What if we have shared the fate of so many interpreters who have thought they saw quite clearly things which the artist did not intend either consciously or unconsciously? I cannot tell. I cannot say [...] In his creations Michelangelo has often enough gone to the utmost limit of what is expressible in art; and perhaps . . .” (I suggest that you read the rest - there)

_ _ _

Michelangelo’s greatness is in all of his work – as not only Freud, but all the witnesses, even those which have disliked him as a person confirm. His greatness was all in his oeuvre, in strange self-awareness, in belief in perfection (of his gift) within an fallible human being. The span of his identity and expression was, and it remains immense – from exchanging punches with Torrigiani to sculpting dreamy Le rime for Vittoria Colona.

The complexity of Freud’s Moses hypothesis, even if not accurate, provides a perfect example of openings to thought provided by encounters with Michelangelo. A story not completely told leaves the gaps, hints for ideas to inhabit.

non-finito – all that matters to us at this moment, here

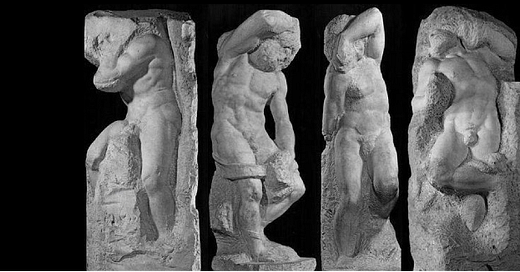

_ _ _ when we line up these four Pietàs, undisputed 1 – 2 – 4 – (and keeping the disputed No. – 3 –) in their historic order (below), there is an obvious sequence, we can clearly see a trend in Michelangelo’s approach; his work evolves from an absolute perfection (in terms of life-like depiction of the figures involved in Vatican, towards rougher (un)finishes, and – to me, this is where subjectivity inevitably has to come in – an amazing increase in the intensity of a message captured in stone); if we applied common logic that IS a paradox; but – as exemplified by our story from the bottega in Florence – while that might be a common logic, this is Michelangelo; what we might be witnessing here is a radical redefinition of what the whole is

_ _ _ for Michelangelo Buonarotti, the point was not in physical likeliness of the outcome (a great anecdote related the lack of likeness of his own, sculpted Lorenzo di Medici and actual Lorenzo has to stay for another time); the point is in contemplative charge captured in the work; for the One who was capable to sing in stone, the challenge was how not to stay confined to stone; Michelangelo seeks full immersion of a viewer, participation, complicity . . . in the case of Pietà, that is participation in the grief of subjects (which, along with an unspeakable beauty, overwhelmed me the first and every other time in San Pietro, even after the protective glass created an unwanted but, alas, in these times needed barrier)

_ _ _ fascinated by each and every of his Pieta’s (all four, I admit; I absolutely understand why the detail of disputed Palestrina Pietà was at the cover page of our book; . . . that tongue . . .), if I had to choose Pietà Rondanini is a true tour de force; and, one must understand that Michelangelo did not want to stop there ... simply, his life has stopped there, then)

_ _ _ Michelangelo Buonarotti sought not a definite the shape, but to liberate us . . . with an opera aperta (as his great compatriot, Umberto Eco was to define more than five centuries later)

notes, scribbled while writing this post

_ _ _ not to finish vs. to finish

_ _ _ to open up vs. to close

_ _ _ to initiate, vs. to conclude

_ _ _ to dream, to aspire (yet, never to reach) vs. to be “realistic” (and never to live)

_ _ _ and now, back to the city _ _ _ non finito and the city, the city as non finito

First time I took non-finito explicitly into my urban design in 1987, in an competition entry for Un’ idea per le Murate, a major urban intervention in Michelangelo’s own Florence. The competition was announced as “un concorso di architettura”, and I have decided to make an entry which would address (what I saw as) an inadequacy of my profession to deal with urban complexity at this scale, in this place. G. and M., my assistants in CEP joined me as willing accomplices, designing all they felt like designing, while to me the message was encapsulated in a simple drawing (above, left), which shows the fabric of Florence integrated with an equally fine yet rough fabric of stone, pietra from which emerges (or in which forever stays) one of Michelangelo’s gigantic slaves. The message was that cities are always non-finito, that they are in constant flux, in search of own (re)definition, and that the (wonderfully prepared and organised) competition brief was – wrong. A youthful arrogance? . . . Perhaps. To me, that was an act of self-positioning, a Dixi et salvavi animam meam moment that I stay proud of.

_ _ _ as stated at the opening, this post has to deliver a rounded story, yet end – unfinished; not finishing (it) was a point

P.S.

a fragment from Le Rime, mentioned above

042

_ _ _ Dimmi di grazia, amor, se gli occhi i mei

veggono 'l ver della beltà ch'aspiro,

o s'io l'ho dentro allor che, dov' io miro,

veggio più bello el viso di costei.

_ _ _ Tu 'l de' saper, po' che tu vien con lei

a torm' ogni mie pace, ond' io m'adiro:

Nè vorre' manco un minimo sospiro,

nè men ardente foco chiederei.

_ _ _ La beltà che tu vedi è ben da quella;

ma crescie poi ch'a miglior loco sale,

se per gli occhi mortali all' alma corre.

_ _ _ Quivi si fa divina, onesta e bella,

com' a sè simil vuol cosa immortale:

_ _ _ Questa, e non quella, a gli occhi tuo' precorre.

> > > or, only opening, only from memory . . .

Pa kazi mi ljubavi

da li je tvoja ljepota stvarna

ili zivi samo u ocima mojim ...

> > > rougly translated > > >

Then, tell me, my love,

is your beauty real

or it exists only in my eyes ...

in memoriam, Vava, a friend and 空手家